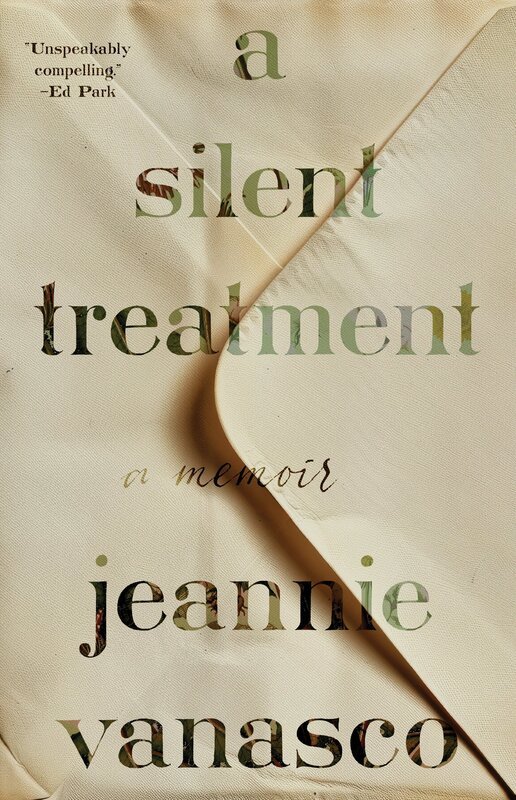

INTERVIEW: Jeannie Vanasco

A Silent Treatment

Jeannie Vanasco

Tin House

An interview with

Alexandra Clemente Perez

If you’ve read anything by Jeannie Vanasco, you know that there’s something about names. I excitedly preordered her new memoir, A Silent Treatment, (Tin House, 2025), in which Jeannie recounts living through a silent treatment by her mother, with whom she shared a house in Baltimore. I ordered from Greedy Reads, a local Baltimorian store. Alex, the bookseller, and I, Alex the bookbuyer, went back and forth with addresses and specifics. Only to have the original copy be lost in the bowels of USPS. But Alex’s have each other’s backs, and I quickly received another copy (also signed!). Before Jeannie agreed to this interview, I thought: This Alex helping Alex subplot would be very at home in a book by Jeannie.

No writer is an island, and Jeannie celebrates that in her work. Her writing-about-writing brings not just her relentless self-questioning to the page, but also her community, who are equally powerful analysts: her writer friends, her partner, Chris, her students, and her cats. And of course, her family.

I talked to Jeannie over Zoom during this unseasonablye cold Bay Area winter about everything from self-help to poetry to comedy to Nicolas Cage.

Alexandra Clemente: It's been two months since A Silent Treatment has been out in the world. How does it feel to have a two-month-old?

Jeannie Vanasco: Oh, God, well, yesterday I woke up at 2:30 a.m., thinking, ‘I am such a bad daughter; I shouldn't have published this book.’ Even though my mom has been in a great mood since the book came out, I still worry that I didn’t portray the complexity of her situation well enough. She said to me, “I’m old. What do I care what people think of me?” But I care. So when a reader says that they would have kicked her out of the house, I think: ‘I wasn’t living in The Real World—the TV show, I mean. I was never going to vote my mom out of the house.’ She was going through a difficult time, and I do think patience—especially with aging parents—is important. But the book is out there, and people are allowed to have the reactions they have, and their reactions are influenced by their life experiences. I’m trying to be more like my mom and care less what people think.

AC: There's a structural difference between this book and your other two memoirs. In A Glass Eye, you focus on your father and your half-sister, who have passed by the time of writing. In What We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl, you interview one of the main subjects, Mark. In this book, your mom is present while you're writing, but she chooses not to be an active participant in the writing or editing process. What did this book teach you about writing memoir that the other two books hadn't taught you?

JV: I realized that to write as authentically and honestly as I could about the experience, I needed to write from within the experience. In the other books, there is a narrative present, but in this one, I'm very much inside the experience as it’s unfolding. In my first book, the struggle to fulfill a deathbed promise to my dad is the narrative present. He’d died a decade earlier. In my second book, my interviews with Mark are the narrative present. He’d sexually assaulted me fourteen years earlier.

In this book, I'm inside one of my mom’s silences, and so my feelings are shifting drastically and intensely. I didn’t know when or if the silence would end. Had I written A Silent Treatment after a silence had ended, I doubt I could have reconstructed those complex emotions. So now I think a lot more about the balance between writing from within an experience and having hindsight. I’d already been through however many silences by the time I wrote A Silent Treatment. So there was some hindsight. Hindsight gave me more compassion for my mom, and I was able to see the humor in our situation.

The silent treatments could be so absurd: during one of them, my mom left a checklist for me to find. It said: 1) call movers, 2) pack. If you're going to move, you don’t need to remind yourself to do those things. Now, of course, some of the book is written from outside of her silence because of the revision process. By working in those two different time periods, this book forced me to ask myself: Do we ever really have perspective?

AC: This is a very funny book. There's that one passage where you try to write looking into the mirror and you’re like, “how self-absorbed is this?” I want to hear about your thought process of adding humor throughout the book.

JV: I was watching a lot of standup comedy and movies to relax. With standup, I started noticing why certain jokes would land and others wouldn't. Some of it had to do with syntax. What I most appreciate are bits where the comedians are trusting the audience. Standup helped me figure out where I could remove the exposition or explanations.

AC: What movies do you remember watching that were informative?

JV: Movies written by Charlie Kaufman, especially Being John Malkovitch, Adaptation, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and, maybe my favorite of his, Synecdoche, New York. It’s a close tie between that and Adaptation. Kaufman shows people struggling to figure out how to do a thing, and they keep getting in their own way, and that feels true to lived experience. Unlike big Hollywood movies, his films have structures that feel, for lack of a better term, “real.” I never once have the experience of, here’s plot point one, plot point two, and so on.

All that said, I did watch some very dumb movies when working on A Silent Treatment. I’d never seen Wedding Crashers, and I don’t recommend it, but it does this flash forward of, I think, six months later, at the end. A lot of movies do flash forwards, especially when the conflict is repetitive, because it gives you a sense that okay, these people have broken out of their destructive patterns and undergone some kind of meaningful change. I’m not saying a book or film requires that people undergo change. But with my situation, I wanted to show that my situation with my mom did change for the better. That’s why, at the end of A Silent Treatment, I flash forward to one year later.

AC: Literary inspiration comes from all sorts of places. I'm a firm believer that there's a lot we can learn about conflict and storytelling through The Real Housewives. Interesting that you mention Adaptation. Nicolas Cage is in it and Nicolas Cage also makes an appearance in this book.

JV: There was way more Nicolas Cage in previous drafts, and I was like, "Okay, dial it back, Jeannie." I had to ask myself: Why do I think Nicolas Cage belongs in this? It started because my mom casually said she didn’t think he was handsome or a good actor, and I rushed to his defense. Until that moment, I could have cared less about Nicolas Cage. Ultimately, he served as an example of how I will argue with my mom about anything just to argue with her. How having my mom in the house caused a regression back into almost, like, adolescent behavior.

AC: In preparation for this interview, I reread all your books. As a career memoirist, how much are you thinking about backtracking into your other memoirs, and how much are you purposefully not including?

JV: I went back and forth about whether to include mention of my half-sister Jeanne. I wrote about her in The Glass Eye. She was one of my dad’s daughters from his first marriage. She died when she was 16. He added the letter i to my name. But he named me Barbara Jean, after my mom, when she was asleep after giving birth. He thought it’d be a nice surprise. I didn't learn my legal name until I was in kindergarten. If my half-sister came into this book, my dad would have to be included, and I didn't want A Silent Treatment to become about my relationship with him. I wanted his inclusion to be primarily about my mom's experience of him. When she was mad at him, she’d write letters for him to find. My dad had saved them in the liner of his wrench kit, and I found them during my mom’s silent treatment—the one that the book describes. In one of the letters, she wrote, "he ruins everything he touches." I immediately thought of my half-sister because I knew he’d blamed himself for her death. I was very angry at my mom for writing that. How could she not have thought about his dead daughter? But I doubt my mom was thinking about my half-sister when she wrote that letter. His daughter died decades before my parents married, and my mom was not that cruel. Because I thought about my half-sister only in that one moment, and because my thinking about her had more to do with me than it did with my mom, I decided not to mention my half-sister. Not including a detail doesn’t automatically make it a lie of omission. A memoir is selective. It has to be. The writer needs to determine what’s right for the story, and that’s very, very hard to do.

AC: In your threads in this book on writing-about-writing, you include your partner Chris and other friends as almost a Greek chorus. They move the story along, they serve as reader surrogates, and they push back on your perceptions. What do you think you get out of adding them in, from a narrative perspective?

JV: Conversations with other people are crucial. They challenge me in a way that I might not even think to challenge myself. I like it when I witness a writer being surprised within their work. I can only surprise myself so much. If I let myself free associate, and I find spaces of hesitation, that's where the surprise happens. But conversations with other people are often more productive. They steer me in very unexpected directions. And this goes back to form. I love the essay form, love reading someone thinking through something. I was recently rereading Montaigne's essay on the inconstancy of our actions. I can't remember the exact wording, but he says something along the lines of our impressions of who we are and who other people are will shift all the time. I think that's why I like the writing about the writing. It reminds the reader that they're reading one person's version of the events.

AC: Speaking of form, I also think of poetry. Your writing is very poetic in its structure, especially in its white spaces. How do you think of poetry informing your memoir writing?

JV: A text that was really formative for me early on was Robert Bly's Leaping Poetry. It's an anthology in which he examines the leaps, big and small, that poets make. I love that feeling in poems when it seems like the subject is getting away from the speaker. Another book that’s great about that is Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town. I’m teaching a graduate memoir class next spring, and I plan to include The Triggering Town. Poetry is so much about what you leave out rather than what you put in.

AC: In that way, poetry is similar to humor: it's the balance of what you leave out versus what you leave in. There is a lot of poetry in humor. The language needs to be very precise in both of them.

JV: The most poetic standup special I've ever seen is Jacqueline Novak’s Get On Your Knees. On its surface, it’s about learning how to give a blowjob. The language is so good. She even fits in a J. Alfred Prufrock allusion—something like, “I had the boyfriend laid out on a bed like a patient etherized upon a table.”

AC: With poetry and humor, we're talking about the precision of language and naming things what they are. I see that as a preoccupation of your work. In this book, you're careful about using the word abuse. In What We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl, you wrestle with the word rape. What power do you think naming things with their correct name carries?

JV: Names have long been a preoccupation of mine, just because of the connections I have to my names, being named after both my mom and my dead half-sister. That preoccupation deepened with getting a diagnosis of bipolar disorder during my senior year of college. I'm really interested in naming, particularly when we treat a name as a form of self-knowledge. What I would see happening to myself and to people around me, especially people I'd meet in the hospital, was that they began seeing the diagnosis they'd been given as a solution that explained all of their behaviors. They started to see any of their actions through that prism. It almost obliterated any sense of free will. I'm not anti-diagnosis, and I'm not saying you can't attribute some cause-and-effect there. But that kind of certainty ended up stifling me. How much do we let a name control our sense of self?

AC: In this book, you do a lot of internet searching, and asking Google Home about how to deal with the silent treatment. It made me wonder what your relationship is to the self-help genre.

JV: So many people find the genre helpful. Personally, I find a lot of it to be very flat portrayals of human beings when it relies on generalizations. I couldn’t find any self-help books focused on the silent treatment, so I watched some YouTube videos. Most of the people said that anyone who uses the silent treatment is a narcissist. I find that accusation both boring and harmful. It excuses the person who's seeking help from practicing self-awareness, from examining anything they might be responsible for. I’m not saying self-help is all bad. When I'm reading self-help or receiving advice from a friend, and then I resist the advice, that's where the essayist type of thinking is important. I ask myself, What it is saying about me that I'm recoiling at this?

AC: With this book, you are doing something so hard: taking your mother's experience and seeing her in her full humanity. You take some of the behavior that feels and is hurtful, and analyze it as part of her trajectory. That's really hard to do.

JV: I'm newly obsessed with the books of Adam Phillips. He's a psychoanalyst who studied English literature. He writes for a very public-facing audience. He had this great aside in one of his books: The art of family life is not to take it personally.

AC: Wow, that's so good. I'm gonna put that on some mugs and give them to my family for Christmas.