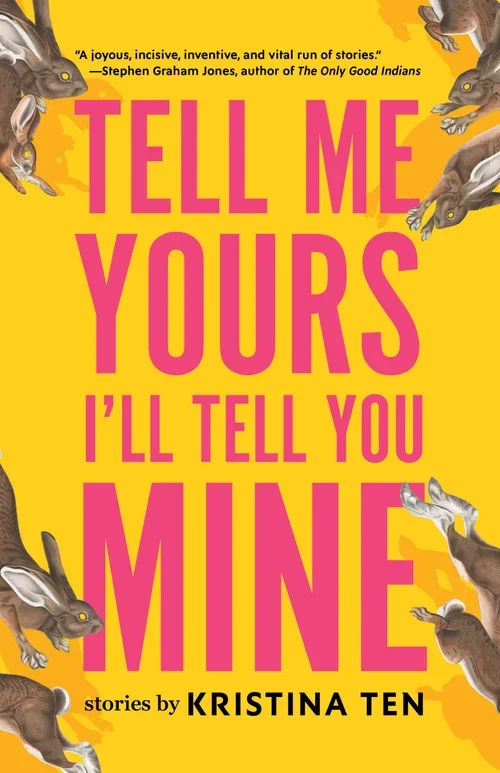

INTERVIEW: Kristina Ten

Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine

Kristina Ten

Stillhouse Press

An interview with Anu Khosla

As soon as I got on Zoom with the writer Kristina Ten, she started telling me about her weekend trip to the Lake of the Ozarks from which she had just returned. She asked me if I had ever seen the shape of this particular lake, which I hadn’t, and encouraged me to Google it. The lake looked like a centipede, very different from the Finger Lakes –– which look like the scratch of a cat –– which she currently lives nearby in Upstate New York. The centipede lake reminded her of “the pomegranate thing,” as she called it, which is trypophobia, or a fear of dots. Right off the bat, Kristina was initiating me in her attraction to spooky things. One could say she had a natural orientation towards the surreal, one that is very much present in her new short story collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine.

Kristina was the kind of person that I could just let go on, taking the conversation on a route as surprising as the Lake of the Ozarks without much prodding. She had an inherent curiosity about things which meant she didn’t really need an interviewer. But still, I was there to interview her, so I figured I should try my best to focus the conversation.

Anu Khosla: What were you like as a young girl?

Kristina Ten: I have a few characters in this book who self-identify as being raised by computers, and I would say that that is what I was like as a kid. I am an only child. I was for sure a very self-conscious kid. I was involved in extracurriculars, I played volleyball like one of my characters and I sang in choir. I really liked the structure of school, but I struggled with the social aspect of school just because I was so self-conscious that it was exhausting to be around other people. So when I had the option, I was a loner, and I definitely hung out more with adults than with kids. I was one of those kids that adults call an old soul. Which I think they meant as a compliment, but they should have taken it as a cry for help.

When I moved to the States I was still speaking Russian at home and was very much Russian culturally with my family. In elementary school there was that tension because even though I had been living in the States for a short while, I was basically living in Russia at home. School felt very foreign to me. I needed to take ESL classes to catch up with the other kids, so I definitely felt on the outside of things. Like some of the characters in this collection, I found some value in games and in childlore, childhood traditions, childhood rituals. I found value in them as a language to connect with the people around me in lieu of having the English language or what I perceived as the more traditional American childhood experience to connect with.

AK: There are different themes that connect these stories, but one of the most obvious ones is that these are stories about adolescence. Why is adolescence a subject that you're particularly interested in?

KT: When I started this collection, I knew that I wanted the linking force to be games and child lore because I had a fascination with them that I wanted to put some pressure on. I wanted to believe that I was fascinated with them not because I was myself childish or experiencing some arrested development or uninterrogated nostalgia, but for some deeper reason. Childhood is a time that we romanticize a lot. When I feel fondly about childhood, it's because I remember it as a time when I thought that there were clear-cut rules that if I followed I would win, or I would do well, or I would at least be safe. As you get older, that promise dissolves before you.

I think about adolescence and speculative fiction on similar planes in that there's a slipperiness, right? You're in between worlds, and it's so thrilling, you feel on the brink of magic. This is a time when you could still believe in impossible things. You could still believe that you have this transgressive power, that if you and all your friends put your fingers underneath another friend's prone body, you, with your collective strength, can lift that person. Or if you and all your friends say Bloody Mary into the mirror three times, you can bring this presence into your home. Adolescence is on the very brink of when it's okay to believe all that before that power is ripped away from you.

AK: The vernacular of these stories is very '90s, and I was curious about the process for developing that. Was it all based off of your own memory, or were there any processes you used to uncover some of the terminology?

KT: I'm sure I did some googling here and there, but it’s mostly from lived experience. I studied with Stephen Graham Jones at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and I experience him as an author who writes the way that he speaks. At least in undergrad, I was taught that you shouldn't do that, that you should aim for this higher level of discourse. The reading that I've done since then and studying with authors like Stephen has given me permission to write closer to the way I speak. Some of the vernacular you're talking about is part of that.

The research element included reading other game-related fiction. The cootie catchers, the paper dolls, definitely the jump rope song, for example, in “Approved Methods”, and other riddles, rhymes, some of the superstitions in here, some of the camp songs like Herman the Worm –– all of these can be identified as '90s artifacts. And that's how I thought of them, too, until very, very late in the process of writing this book, when I came upon the term childlore, which was coined by Iona and Peter Opie. They were folklorists, and they coined the term and wrote a lot about childlore, which is the folklore of children. It is specifically folklore that is learned by, passed on, and taught to children by other children. Adults are not part of the equation. It is this secret world that belongs only to kids.

The idea of childlore is that it is fluid geographically and temporally, so it's curious that a seventh grader in California and in Nebraska are both drawing in their notebooks that cool S, if you remember that cool S. It's curious that someone in the '80s and someone in the early aughts, 20 years apart, are both drawing that S, and adults have no idea what it means. A teacher didn't teach them to do that. That just permeated the culture of children and traveled via cousins and new kids in school.

AK: Now that I'm hearing this term childlore, it does feel like this idea is having a cultural moment right now. Do you have theories about why that is?

KT: One theory that isn't mine is that culture comes back around every 20 or 30 years. Do you remember those popcorn shirts? Those teeny tiny popcorn shirts? They were this big, and they're made of this shrinkable fabric. The idea is that it stretches to fit almost every body type. I saw one the other day in a store and experienced this full-throttle time travel. Things like the clapping games, things like the paper dolls with the tabs, those are very analog, and we are so deep in a digital landscape.

Right now, I don't live close to an in-person writing community, and so I do a lot of connecting via Zoom, via Discord, via Slack, via social media. It's a beautiful thing. At the same time, we're so locked into our screens. We are having to constantly reprogram our brains to scroll past the AI overview on our Google searches. We're learning how to identify AI in photographs so that we can know what's real or not.

I've definitely heard a lot of people craving for the Wild West of the early internet –– MySpace, GeoCities, Angel Fire –– back when the internet didn't feel like this place of constant advertising, constant surveillance, and felt more like a joyful playground where you could build something if you just learned some basic HTML coding. I think people are craving more analog in their lives, and interactivity, too. Even some of the stories that I read researching for this collection that exist on a digital plane, they're published online, but they take the shape of a pop quiz or a choose your own adventure. There's an interaction. There's agency. I also read some books that are physically reaching for a more analog feel. Like GennaRose Nethercott has a book in cootie catchers. And then Jedediah Berry has a book, The Family Arcana, that's told on playing cards.

AK: Earlier this summer, right before I read the collection I was at a wedding in Upstate New York for a close friend. When we sat down at the wedding, they had a Mad Libs for everyone to fill out. You put it in a basket and returned it to the couple so they could read it on their honeymoon. I had read that particular story of yours, with the Mad Libs, before the full collection. Where did that story come from?

KT: I think that's really cool. At our wedding, we had those paper placemats that they give kids at Applebee's. It had crosswords and connect-the-dots and stuff. I love that adults are reaching for playfulness. There's an artist that I really like called Britchida, and she uses a lot of interplay between text and image in her work. She has a piece from years ago that I was referencing when writing this, and it says, “Play is the opposite of survival mode.” I think about that a lot when trying to bring playfulness into my life more. I am really drawn to found forms and to working within an existing structure. Sometimes it's something firmer, like Mad Libs, and sometimes it's just like, in the case of “Seven Days”, that story, the structure is anaphora. This is only going to cover seven days. Every day is going to start with the same words. I find it useful to operate within that blueprint. It makes writing the story feel like a puzzle, which tickles the right parts of my brain.

For that particular Mad Libs story, I knew from the get-go that I wanted to write about self-perception and self-definition, and how to fight against other people's perceptions and other people's impulse to define who you are and to be able to assert yourself and say, “No, this is who I am.” I thought that Mad Libs would be an appropriate form to think about agency. A lot of the collection deals with control, and a lot of it is control over someone's physical body in the form of reproductive laws, or in the form of rules about weight loss, say, on a volleyball team. For this particular story, I was thinking beyond the physical body and more about our ability to self-identify. So in that story, a pesky new coworker is just playing devil's advocate with the protagonist and saying, “Are you really an immigrant?” I was thinking, how can I make the reader feel the way that this protagonist is feeling? The Mad Libs fields prompt the reader to make a choice that, in theory, influences the movement of the story forward or influences the narrative that takes place. At the same time, that choice is limited by whatever is already in the prompt.

AK: I noticed you’re wearing a cap that says “short stories” on it. Can you talk to me a bit about your philosophy of short stories?

KT: Yes. Shout out to Electric Lit, where I got this hat. My philosophy is that short stories are an amazing ground to do whatever the hell you want because you don't have to commit a novel's amount of time and words and plot to a short story. I am in the midst of doing developmental edits on a novel right now, and it's the first novel I've ever written. I've written tons of short stories, and it's such an interesting challenge and a totally different animal.

With short stories, it often starts with a single line. I come from poetry. When I was living in the Bay, I actually wasn't writing fiction at all until the tail end. I moved to the Bay and became totally enamored by the amazing, vibrant lit scene, which, at least as it came to me at that time, was performance poetry-based. Even though I had only written angsty teenage poetry to that point, I was like, I want to be part of this world, I want to hang out with these people. And so I started writing poetry. I still am very devoted to language, what language sounds like when it's read aloud.

So often an opening line will just rattle around until I build a story around it, or it'll start as a single image, or as some metaphor or allegory. I think a lot about what speculative fiction affords us in terms of reflecting on our current times. In these stories, it's been useful to be able to look at something that's going on in my life or that has happened to me or that I'm watching happen and create that distance through speculative fiction and see if I can see anything more clearly. I'm thinking of “Last Letter First”. I wrote it around the time of the dismantling of Roe v. Wade, but it's not set in our current time. It's set on this Airbus in some post-climate disaster future. But it's the same fight that we're fighting now and the same fight that we were fighting 50 years ago and 100 years ago because these things are cyclical.

AK: I think it's the shortest story in the collection where you talk about Brecht's alienation effect, wherein the playwright would introduce an unfamiliar feeling to familiar situations, in order that the audience could observe them with critical thinking rather than immersion. Could you tell me more about this inclusion? Do you have a theater background that led you to Brecht?

KT: I've heard that the first few chapters of your novel should give readers the key, the tools that they need to understand how to read your book. This was my application of that guidance to this book. I do not have a theater background. I have terrifying stage fright. I think I was in a couple of middle school productions, including a production of Robin Hood. I was Little John's Wife, and I had two lines, but one of them was the very first line of the entire play, and it was terrifying.

I’m going on tour for this book. I'm sure the stage fright will follow me there. But when I'm talking about theories of alienation versus closeness and affiliation, I'm thinking about speculative fiction. I placed that in the center of the collection to act as an echoing off point of the first story, which is also quite short. Hopefully, it also offers some key for how to read the stories to come, or at least acts as an expectation setter. I think of it as similar to the volta in poetry, that turn at the center of a poem, the hinge after which things somehow change.

AK: Can you tell me about your attraction to the surreal in writing?

KT: It really is the only way of writing that makes sense to me. I was challenged writing the novel that I'm currently working on because one, it was my first novel, and two, I, for the first time, learned about things like beat sheets, and the three-act structure, and tropes, and reader expectations in certain genres, and how to cue genre to readers and deliver on the promises of that genre. Which is not to say that every novelist needs to be operating within the three-act structure. I really hope that we don't. But that was the challenge that I posed myself with the novel.

With my short stories, a lot of them mix genre and dip into this surreality just because that's what comes naturally to me. I've always felt in between things in a lot of ways. I've moved around a lot, so I don't have a fixed sense of home. In terms of sexual identity and cultural identity and national identity, I am someone who is between places and of multiple places. And so sticking to a single genre or sticking to, quote, realism, feels totally foreign to me. Because to me, the surreal is real. That's how I am experiencing the world.